Holly Beeston interviews Billy Barraclough ahead of the launch of Murmurations second edition

Throughout the lockdowns and periods of isolation brought about during the Covid-19 pandemic, the question of how to make new and exciting work remained present - a lack of human connection, inspiration and structure took its toll on the creative world. Billy Barraclough, a British photographer whose work centres around the relationships we hold with our surroundings, was able to find some clarity and respite during the lockdowns. Visiting the same murmuration site everyday, a routine of ritual and reflection, Barraclough creates a visual record of his encounters with the starlings, and in doing so, uncovers a spiritual and meditative space for reconnection and introspection. Set against the backdrop of this global crisis, Barraclough invites us to join him in the study of shape and form, instinct and movement, while simultaneously reminding us of a world totally unaffected by the pandemic.

In this interview, Barraclough dicusses his process and approach to creating Murmurations. The interview is released just ahead of the launch of the second edition of the book, which is on presale until 3rd March at a reduced price, and is accompanied with a limited postcard print. Head over to our shop to reserve your copy.

Image above - ©Billy Barraclough, from ‘Murmurations’

Holly Beeston: You began your higher education with a BA in International Development and Economics, what drew you to photography after this? Does your BA ever play into the way you consider the visual arts?

Billy Barraclough: When I finished school and decided to go to university I found myself at a bit of a crossroads. I’d been taking pictures incessantly since the age of 14 but I was unsure about the idea of someone teaching me how to take pictures. I was keen on continuing to be led by my own intuition and knew that whatever I ended up studying I would always take pictures alongside. I had a few conversations with family friends and photographers and they explained the value of studying something other than photography and allowing that subject to inform my photographic practice.

International Development and issues of global inequality felt like quite a natural step for me. My family had worked for charities such as Oxfam, and I was interested in the question of whether we have a moral obligation to help others and how we go about that in the most ethical and effective way. And so International Development was the choice. I continued taking photographs throughout my studies, and explored the role of photography in international development during my degree, but always had the plan in the back of my mind to do a masters in photography. I knew what I wanted to take pictures of, and I was in a place where I wanted some guidance, support and teaching to inform my practice.

My first project, I Trust in God (2016-18), was made in Lebanon. My studies really informed my practice in this project through thinking about ethics, approaching subjects in foreign countries for portraits and making work as sensitively as possible with the wants of the subjects close to the process.

But I found after having made that work I began to really question the power dynamics at play, even having approached it so sensitively. My studies and awareness of representation and the history of the region created a growing discomfort and nagging question at why I had the right to make that work, why should I be saying something about a place I (comparatively to a local) knew nothing about.

Now I find myself in a place where I’m making pictures about things that I know, in a place I recognize and understand, and with a full awareness that anyone I make pictures of is aware of what’s going on.

HB: Your recent project, John’s Notebooks, explores the relics of your late father, a photographer and writer himself, how has his legacy influenced your approach to this project?

BB: I have this one memory when I was young – maybe 4 or 5 – and my father and I were walking on Blackpool beach whilst visiting family at Christmas. We were near the pier and the tide was really far out and I remember seeing thousands of small blackbirds flying together. My father asked me to chase after the birds as they danced in the air above us. I remember him snapping pictures of the birds and I on the big grey expanse and the collective sound of the birds’ wings as they turned the sky black.

It was just before I started taking the photographs for this project that I discovered the pictures from this memory in my father’s archive. I suppose when I started going to see the murmurations this last winter, the pictures of my dad’s and that memory made me consider the birds much more than I would have done previously. They felt an important symbol and memory to reconnect with. It was nice photographing the same thing my father had photographed. It felt like I was seeing the world as he saw it and experienced it. We were almost doing something together that way.

HB: You shot this project within the context of a global pandemic- during a time of sanitation, isolation and regulation. How did your encounters with this entirely natural event affect the way you perceived the pandemic?

BB: Nice question. The pandemic and the resulting lockdowns and isolation made it feel as though the world had changed dramatically and so quickly. We were spending all of our time inside, locked away from friends and family and really felt like the normal functioning of the world had changed without any clear end in sight.

Image Left - ©Billy Barraclough, from ‘Murmurations’

Image Right - ©Besides Press, book spread from ‘Murmurations’

Spending time with the murmurations made me realise that actually the world hadn’t changed as much as it seemed. The ‘normal’ functioning of nature and the environment had continued and despite our lockdowns, wearing masks, sanitising everything and moving across space with anxiety, the trees were still losing their leaves, the birds were still migrating for winter and the murmurations were still happening in the same place and same time every day. There was a regularity and repetition to this process that was comforting. Despite the madness in the human world, the starling world was still functioning. And without being able to spend time in it and with it, I think I would have found the winter lockdown a lot harder to endure.

Having something to attend that had a time stamp – in the absence of a commute, or going to a lecture, or running for a bus – also gave me a purpose and something to anchor my day around. It was something that always happened, despite the weather or pandemic, and that really helped me establish a routine and focus on my time.

HB: The work draws on the parallels and juxtapositions that lie between the natural world and that of our own, is this something you often seek out in your practice?

BB: Jason Fulford talks about photographers either being sculptors or collectors. I definitely see myself as the latter. Photography that involves collecting things, people, and landscapes naturally comes to be about our connection to the environment around us, wh

This body of work, despite being so simply about the shape, form, and scale of murmurations and the way in which they progress from start to finish, also touches on connections and disconnections between the human and natural world. One of which, during the pandemic specifically, was the ability to come together and converge as a crowd or group.

Images - ©Billy Barraclough, from ‘Murmurations’

The work also quite simply pulls on my connection and closeness to nature during this period. Not being able to travel beyond my neighbourhood and see new things made me pay such closer attention to smaller changes happening within the environment around me. I’d never felt so closely drawn to observe the processes and changes in nature - the different birds that would come into my garden, the way the weather affected the murmurations, and the way the trees and hedges were changing as Spring came around. That attentiveness to see something new and different was reflected in this project where I obsessively photographed the same occurrence nearly every day. Marking the changes in their numbers, their behaviours, their roosting spots and so on. The work feels like a study of a murmuration, almost scientific in its approach, and I feel like a project focusing on such a macro subject might not have come about otherwise.

But to answer your question, I do often feel something I seek out in my work is our relationship with the environment around us. Whether this is more first-person like with this project, or more third person, I feel like my work will continue to sit within this space.

HB: The medium of Photography is often one of solitude and meditation, how did this influence the way in which you approached the work itself?

BB: Yeah I agree on this point. I felt like this was taken to extremes with this project too. I would most often go to the murmurations by myself. And during the winter lockdown I would quite often be able to experience them alone without any other bird watchers due to the restrictions. So, it often felt purely me, my thoughts and the birds.

This experience of real solitude during shooting influenced my approach. It feels like there’s minimal distractions in the work – no people, much shrubbery, the absence of colour – maybe it was this experience of solitude, the ability to not get distracted, that made me really dial down on the type of images I wanted to make.

HB: What urged you to shoot in black and white?

BB: Shooting in black and white allowed me to dial down on the form, shape, mass, flow, weight and direction of the birds. I was also keen on the book mirroring the progression of a murmuration from start to finish, and shooting across a whole winter in colour would make that sequence hard to replicate if the sky was constantly changing colour from page to page.

The book has almost only two tonal elements – the black of the birds and the grey of the sky. The lack of real tonal depth was one of the factors that led to the idea to incorporate poetry in the work. There was a similarity to free-verse, sculptural poetry. But I also think shooting in black and white allowed for a much better feel for the movement of the birds. You can really get a sense of how they’re flying, the ebb and flow of their formations across the sky and the shapes that they pull into as the murmurations progresses and intensifies. I hope the sequence and tone of the imagery allows the reader to start filling in the gaps and imagining the way the birds moved between the frames; how their wings collectively sounded, how the sky darkened as dusk pulled in, how the quiet filled the air as they filtered down to roost.

HB: The work is now being somewhat punctuated with poetry, is the written word something you contemplated while shooting the project? What do you hope the poetry will bring to the work?

BB: I wasn’t thinking about poetry whilst shooting. The idea came once Spring came around and the murmurations had started to slow down. Reflecting on the images, I kept thinking about how the sky was like a page and the birds like words scattered across it. This made me interested in how text and this type of image may work alongside each other.

Working with Lue on the poetry, there was the hope that their writing would pull on similar themes in the work whilst not directly responding to the pictures of the murmurations themselves. As for subject matter, I was keen on Lue drawing from their experience of watching murmurations over the same winter. Rather than saying what they should be about, I was hoping for the poems to bring a rhythm that echoed or pulled on the experience of watching the starlings.

HB: Can you talk a bit about the edit and what you hope to evoke? What can the readers expect to come away with after seeing the work in book form?

BB: I wanted the edit to mirror the whole process of a murmuration; starting off quietly as the birds gingerly start to come together; building in weight and scale as the starlings begin to pull into shapes and fill more of the sky; then reaching a crescendo when the weight, noise and mass of the birds almost blocks out the evening sky; before, finally, the performance is over and the birds start to filter down from the sky to roost in the reed beds. I wanted the sequence of images and texts to mirror this bell-like shaped curve in terms of the performance of a murmuration and the calm, quiet reflection after the show. What they reflect on I don’t know right now – but I can’t wait to find out.

Murmurations by Billy Barraclough is published by Besides Press. The second edition is avaiable for pre-order via our shop until 3rd March.

Murmurations (Second edition)

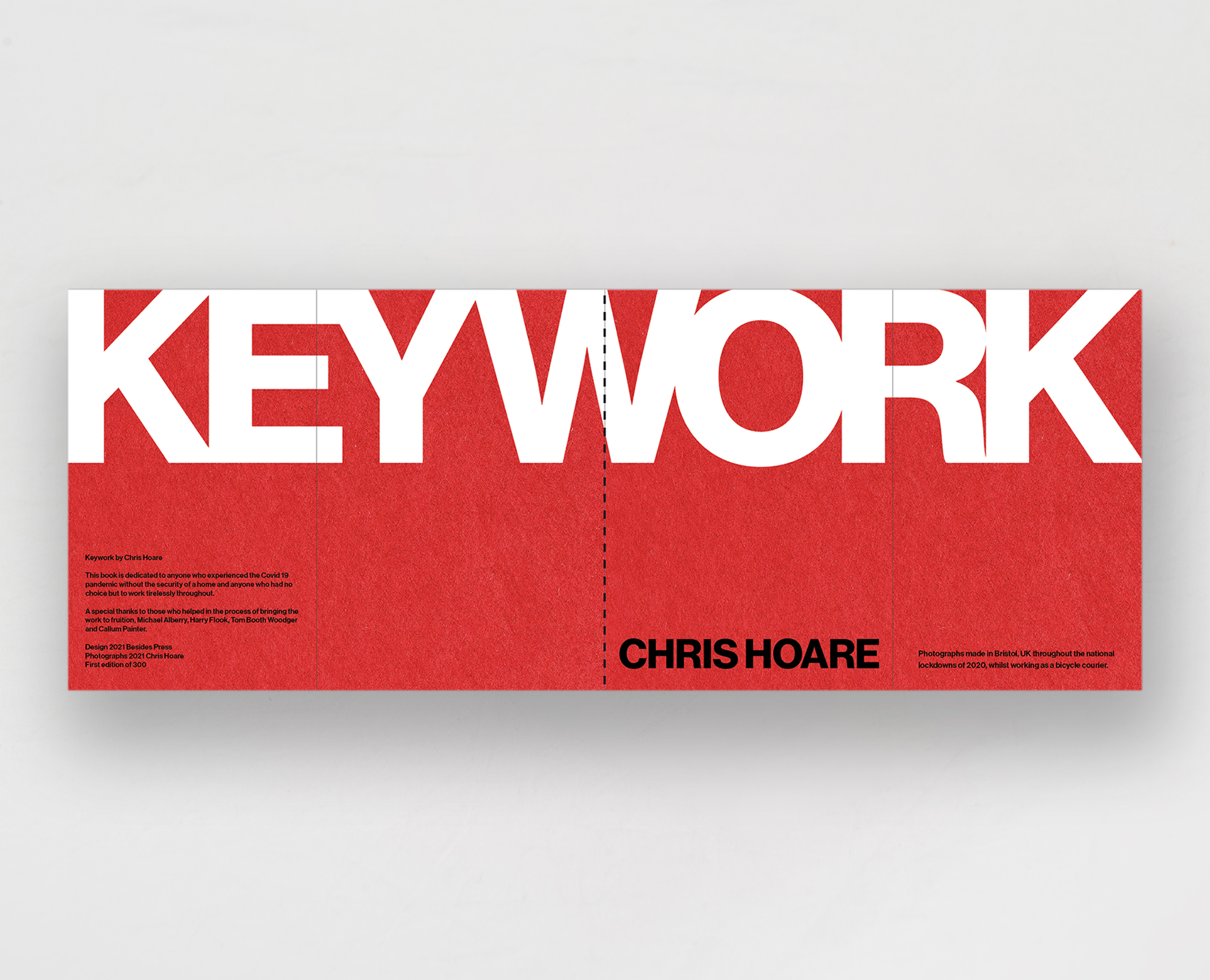

Murmurations (Second edition) Keywork

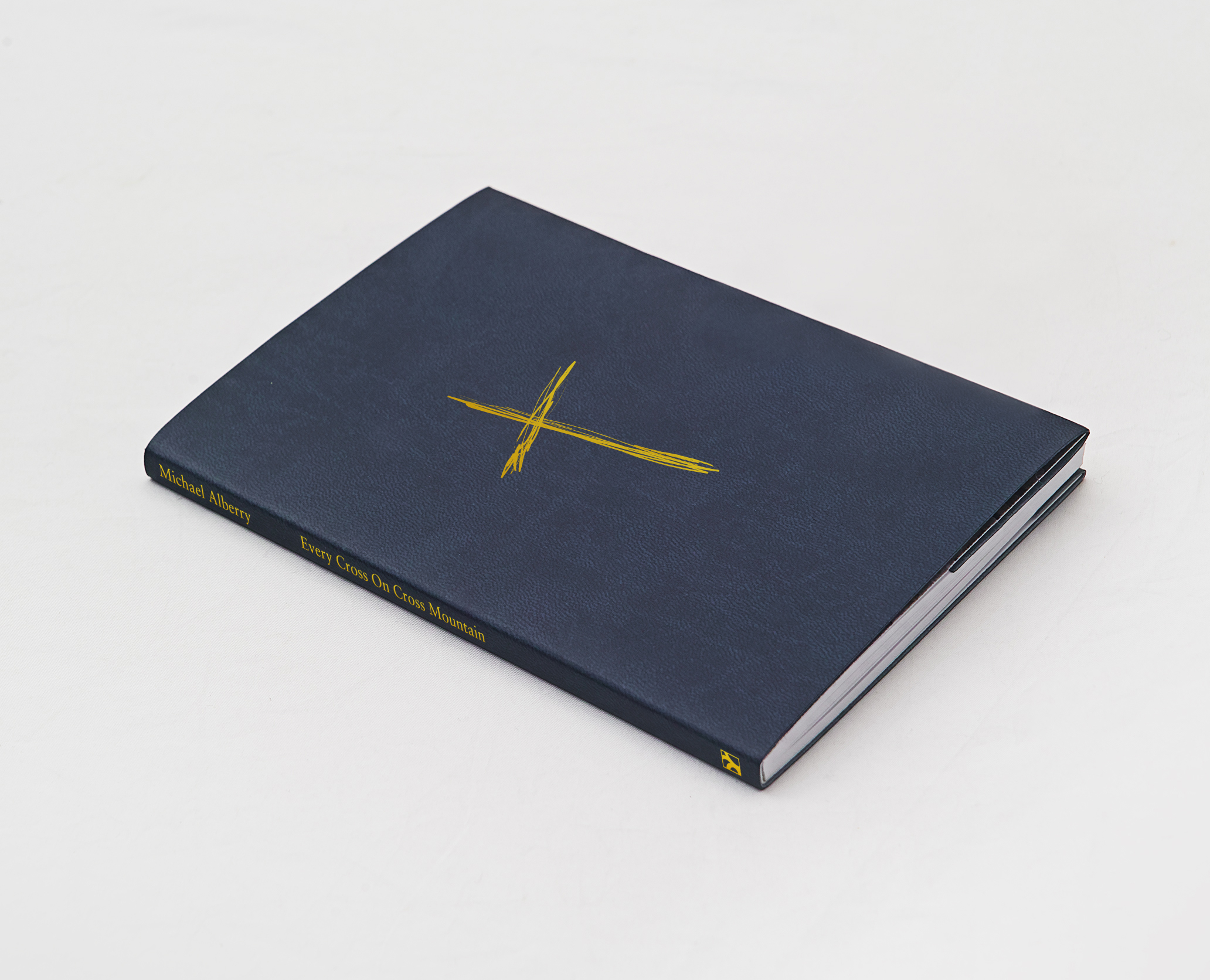

Keywork Every Cross On Cross Mountain

Every Cross On Cross Mountain Murmurations (First edition)

Murmurations (First edition)