Photography in a Time of Loss,

by Lue Mac

by Lue Mac

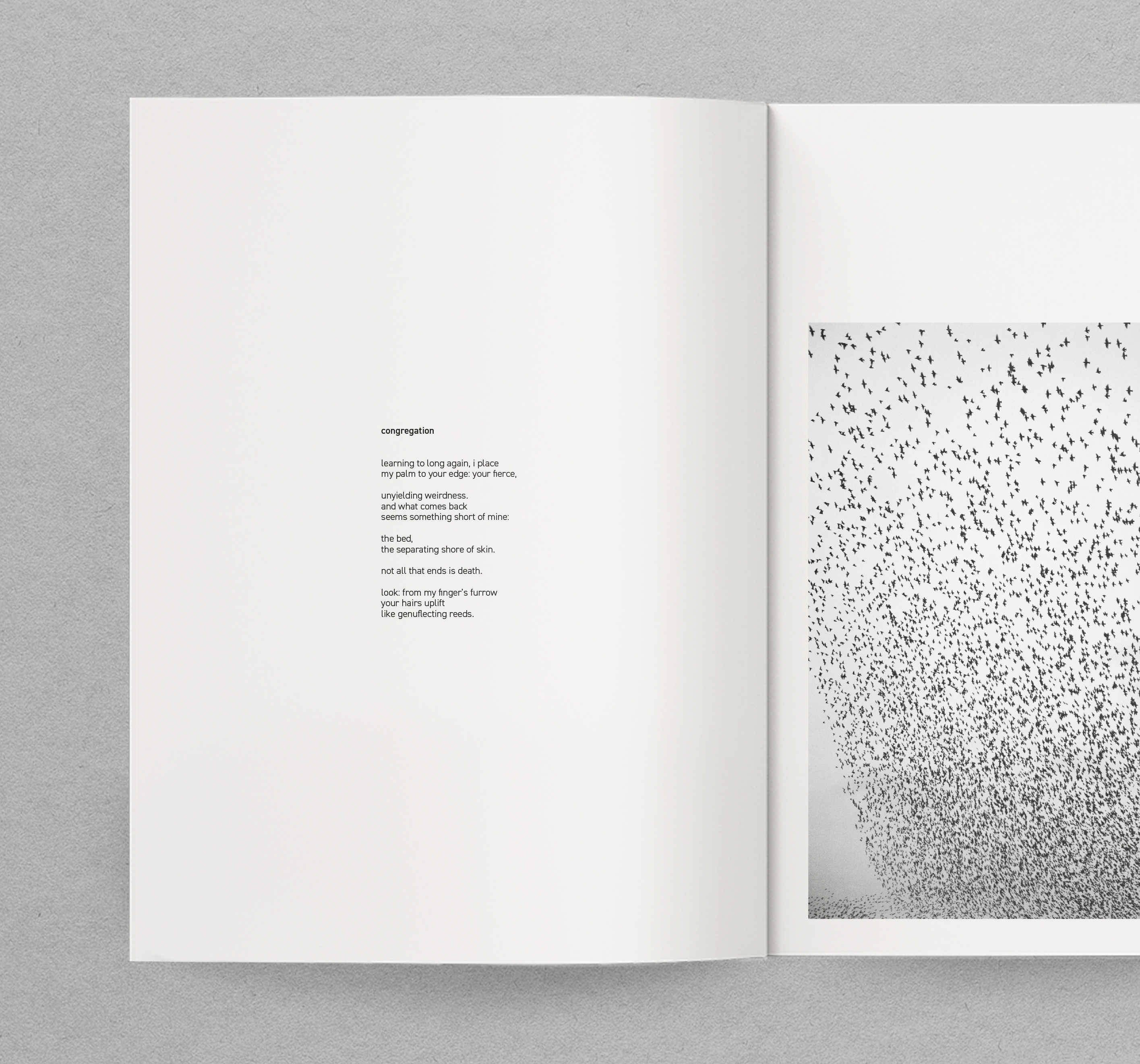

Poet and teacher Lue Mac reflects on their practice through a meditation on photography and loss. This talk was given during syposium of talks which accompanied the launch of Besides Press. Mac’s poems are featured in alongside Billy Barraclough’s images in the book ‘Murmurations’, the second edition is available now via our online shop.

When Besides Press first raised the idea of me writing some poems to go alongside Billy's photographs, we decided early on that they would not be about starlings. This would have seemed too obvious, too lacking in spontaneity, as if the poems were just going to be tacked on at the side of the photos like an arrow, pointing - look, here are some starlings, they can be told in words as well.

That left me with the more difficult (though more rewarding) task of having a kind of conversation with the images. Not speaking over them, not commenting on them, but talking to them on equal terms. Not even, perhaps, being ‘about' the same thing, but being about their own thing in such a way that the images were drawn into an answer.

I thought - as we are talking about photography today - that I would try and talk about my poems in terms of photography, or at least in terms that a photographer would understand. I see this also as being in the spirit of the collaboration that took place between Billy and myself, between two artists speaking in different languages, at different times, and yet, somehow, to each other.

I want to oppose two ideas of photography, two ‘fantasies’ as they would be called in psychoanalytic theory. One of these is represented by my take on Roland Barthes’s Camera Lucida. The other will hopefully share some resonance with my poems from the book.

In Camera Lucida, Roland Barthes describes photography as a kind of wound (’une piqure’ (49) at one point, which means a prick or a sting, as in the sting of a wasp). Here Barthes is punning on the pin-prick aperture of the pin hole camera - the piercing necessary to let in the light - but, it soon becomes clear, he also means it literally. For him, we learn, photography is inseparable from pain. A photograph places its subject before our eyes in a blinding revelation, an excess of reality, but at the price of this reality’s absence. What is preserved in the photograph is not the thing or the moment, but the trace of what the thing or moment was and will never be again. The opening of the camera onto the world would then appear as the cause of the world’s loss. By seeking to preserve, we succeed only in fixing a shadow. The blinding presence of the subject, as revealed in the photograph, is unbearable because it is an endless present-perfect iteration, an endless ‘this has been’. Not quite the past, but in no way the present either, or only in so far as it is a zombie, a death that continues to die.

So for Barthes, the opening up of the human subject onto the world is coterminous with suffering. We suffer because we are open. By letting the world in, by being porous, we make ourselves vulnerable to harm. What starts as a pin-prick can soon widen into a rift, a crater, a black hole.

And so far I agree with him. To be open is to suffer. To let the world in is to lose control of your boundaries, to begin to become something else. When one strand of this connectedness snaps, we end up feeling less as a result. Where I depart from his conclusions is over a) whether this is avoidable and b) whether that is all that openness can achieve. Might our leaky apertures leave us with something more than a shadow?

To stand as a counter-fantasy to this rather bleak vision, I would offer these words from Judith Butler:

‘Let's face it. We’re undone by each other. And if we’re not, we’re missing something. This seems so clearly the case with grief, but it can be so only because it was already the case with desire. One does not always stay intact. One may want to, or manage for a while, but despite one’s best efforts, one is undone, in the face of the other, by the touch, by the scent, by the feel, by the prospect of the touch, by the memory of the feel. And so, when we speak about ‘my sexuality’ or ‘my gender,’ as we do and as we must, we nevertheless mean something complicated that is concealed by our usage. As a mode of relation, neither gender nor sexuality is precisely a possession, but rather, is a mode of being dispossessed, a way of being for another or by virtue of another.’ (23-4)

To be myself then, according to Butler, is only possible because I am already, irrevocably, what I am not. Just as a photograph cannot exist without the presence of what is not there, so I cannot exist without being undone by the ways I combine and come apart with others.

I think from one perspective, the lockdowns artificially created the conditions under which what often gets called the ‘liberal' subject could become a reality. The liberal subject is the individual, the body existing independently of other bodies, responsible for itself above all. From our various confinements, it might have made sense to think of humans as fundamentally separate - particularly when faced with reminders of the exorbitant price of caring for people that we go on to lose, and of the real risks associated with letting foreign bodies under our skin.

But from another perspective, I think we’ve seen irrefutable evidence of the ways we only exist 'for or by virtue of' others. Whether this is the network of labouring bodies who fill our shelves every day and take care of us when we are sick, or the family members and loved ones whose faces are as nourishing to us as food and water, we have been shown proof that dependency and openness are not something we can ever do without. Nor would we ever want to anyway! The alternative would be to become a hermetic chamber, a nuclear bunker, a literal camera obscura. But not a living being in this messy, entangling world. Without the wound of the aperture there is no loss, this is true - but there is also no photograph. And without being undone by beauty and desire, as we all now know, we do not last very long.

References:

Barthes, Roland, Camera Obscura: Note sur la Photographie (Paris: Gallimard Seuil, 1980).

Butler, Judith, Precarious Life: The Powers of Mourning and Violence (London: Verso, 2004)

The second edition of Murmurations by Billy Barraclough and Lue Mac is available for purchase via our online shop.

Murmurations (Second edition)

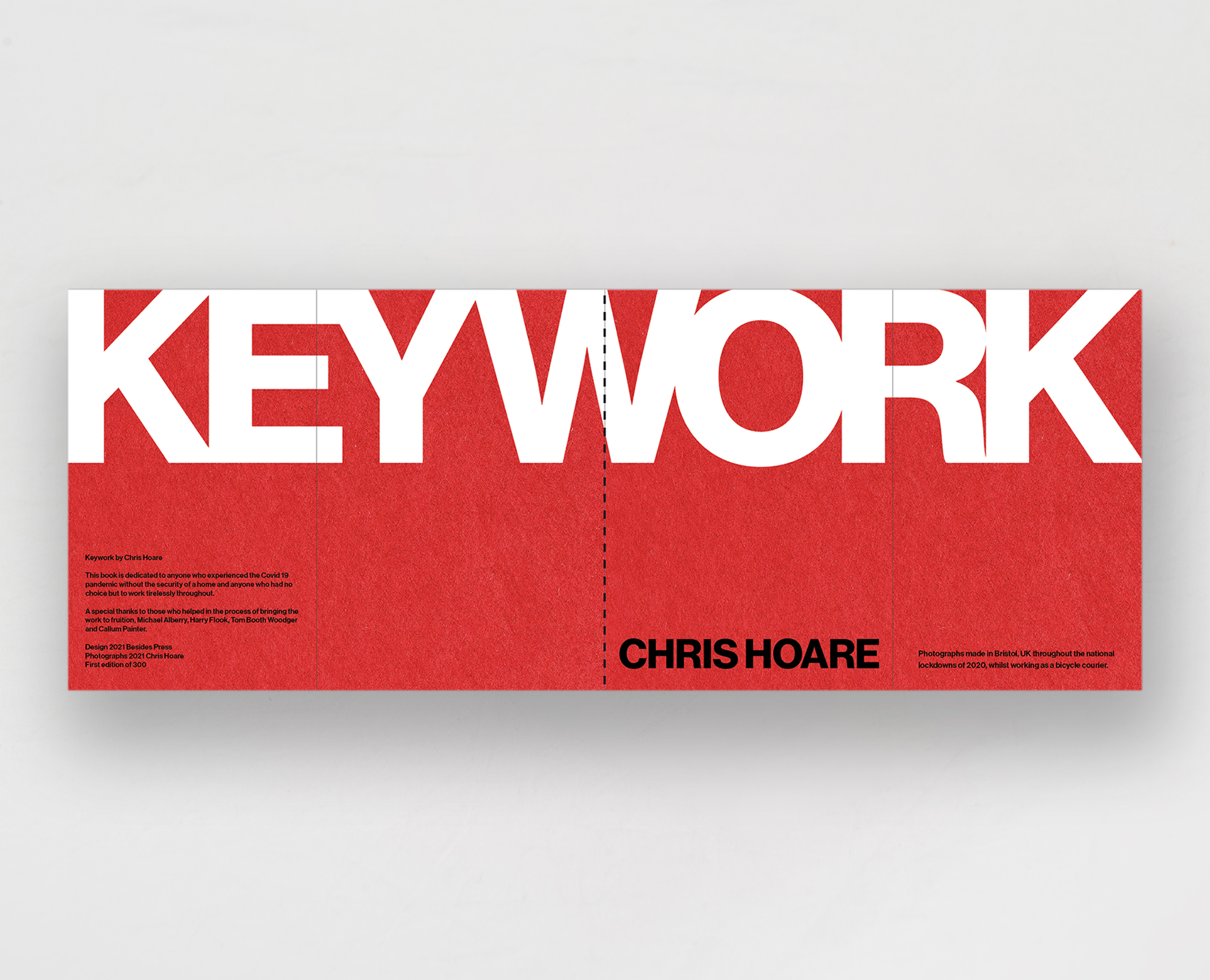

Murmurations (Second edition) Keywork

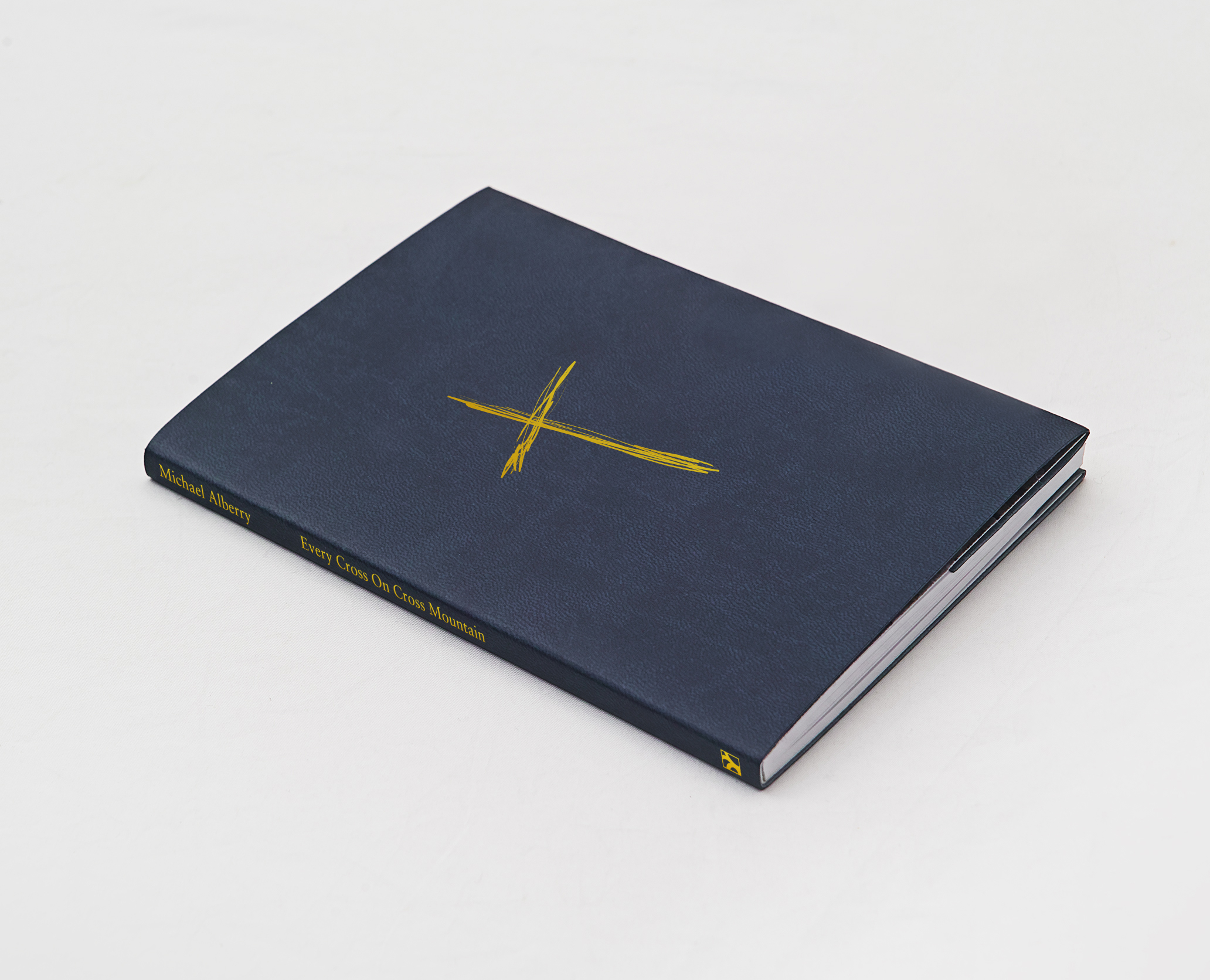

Keywork Every Cross On Cross Mountain

Every Cross On Cross Mountain Murmurations (First edition)

Murmurations (First edition)